Graphs and Tarjan’s Algorithm

Untangling Python projects with Rust

Graph theory provides a mathematical foundation for understanding structural relationships between entities. Directed graphs, in particular, model asymmetric relationships such as dependency, ownership, and communication. Within this framework, strong connectivity, the property that every node in a subset can reach every other node, plays a central role in reasoning about cycles, modularity, and causality. In graph theory, a subgraph is strongly connected if it is directed and if every vertex is reachable from every other, following the edge directions. It’s defined as weakly connected if it is undirected or if the only connections that exist for some vertex pairs go against the edge directions.

Tarjan’s algorithm is an elegant linear-time method to identify strongly connected components (SCCs) in directed graphs. It underpins essential infrastructure in compilers, static analyzers, and dependency management systems. In software analysis, directed graphs arise naturally from imports, function calls, and data dependencies. Recognizing cycles within these graphs is critical for incremental computation, correctness, and maintainability.

Today I’d like to outline the algorithm’s structure and theoretical basis, then examine its application in the context of Beacon, a Rust-based Python language server that I’ve been building. Beacon’s workspace module treats source files and imports as a dependency graph. By integrating Tarjan’s algorithm into this architecture, the system achieves deterministic incremental analysis and reliable cycle detection without resorting to ad hoc heuristics. It offers us a simple yet powerful way to partition such graphs into strongly connected components using a single depth-first search (DFS).

Theory

Strongly Connected Components

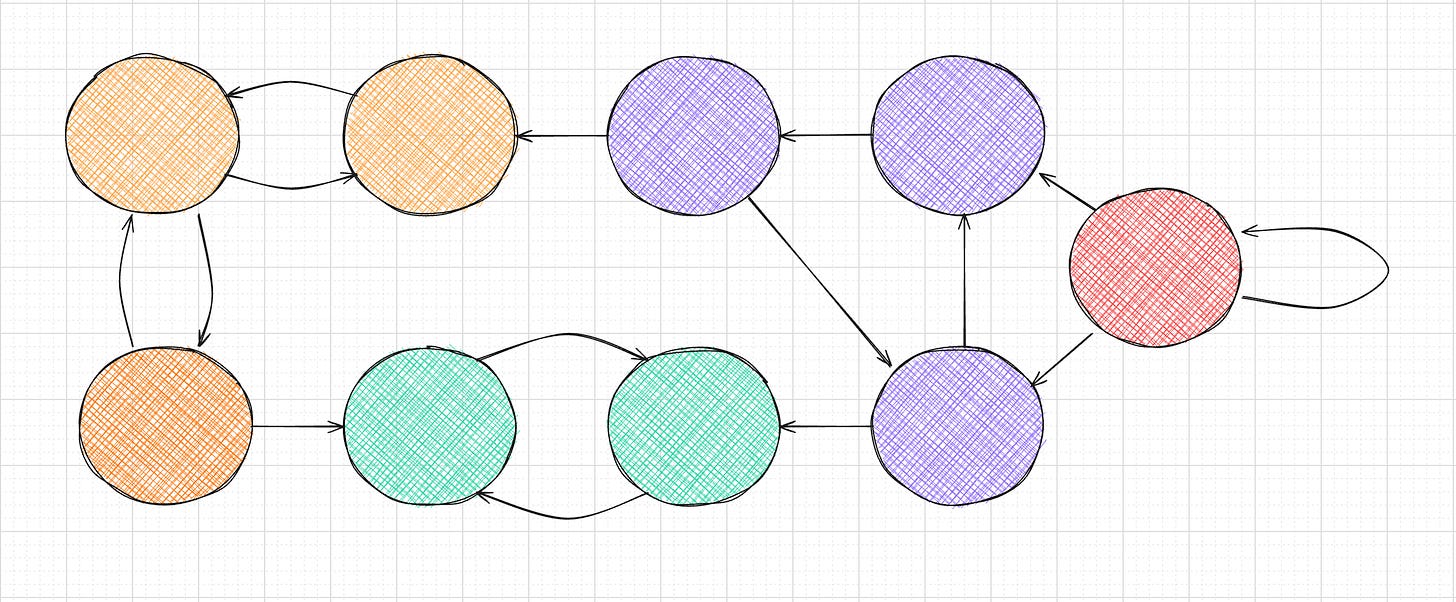

Given a directed graph G = (V, E), a strongly connected component (SCC) is a maximal subset C ⊆ V such that for any two vertices u, v ∈ C, there are paths from u to v and from v to u. Collapsing each SCC into a single node produces a condensation graph, which is acyclic by definition. This transformation simplifies reasoning about dependency order and incremental updates.

A directed graph can be thought of as a set of points connected by one-way arrows. A strongly connected component (SCC) is a group of points where you can follow the arrows in some direction and always find your way from any point in the group back to any other point. If you shrink each of these groups down to a single point, you get a simpler version of the graph called a condensation graph. This new graph never has loops that let you return to your starting point. It always moves forward. That property makes it easier to understand how parts of a system depend on each other or how changes can be mutated in order. In software systems, SCCs represent groups of mutually dependent modules, so detecting and collapsing these cycles allows systems to analyze or rebuild only what is necessary.

The Algorithm

Tarjan’s algorithm identifies SCCs with linear time complexity (O(V + E) → O(N)), through a single depth-first traversal. It maintains the state as:

index[v]: the order in which node (v) was discovered;lowlink[v]: the smallest discovery index reachable from (v), including back edges;A stack to record the current search path.

During traversal, each node is pushed onto the stack when it’s discovered. If we encounter an edge to a node already on the stack, it updates the lowlink value to the smaller index, recording a back edge. When index[v] and lowlink[v] are equal, the node is identified as the root of a strongly connected component; nodes are popped until that root is removed, forming a single SCC.

procedure strongconnect(v):

v.index = index

v.lowlink = index

index += 1

stack.push(v)

v.onStack = true

for each (v, w) in E:

if w.index is undefined:

strongconnect(w)

v.lowlink = min(v.lowlink, w.lowlink)

else if w.onStack:

v.lowlink = min(v.lowlink, w.index)

if v.lowlink == v.index:

pop vertices from stack until v is popped

output these as one SCCThese SCCs can be generated in reverse topological order of the condensation graph. In other words, from components with no outgoing dependencies to those that depend on others.

This ordering is especially valuable in contexts such as dependency analysis and incremental scheduling, where processing components in dependency-resolved order ensures that each component’s prerequisites are handled before its own. In practice, this allows systems to update/recompute only the affected parts when changes occur, without reprocessing the entire graph. These features were paramount when traversing and analyzing Python projects with Beacon.

Python Workspaces as Graphs

A Python project can be interpreted as a directed graph where each module (file) is a node and each import statement forms a directed edge.

However, Python’s flexibility complicates this process. Imports can occur at runtime or conditionally within functions, and the distinction between source and stub files (.pyi) adds further complexity. A naive linear scan or heuristic ordering easily leads to inconsistent states or redundant reanalysis.

Beacon addresses this challenge by constructing a live dependency graph that represents the workspace as it evolves. Every edit, file addition, or configuration change updates this graph. Tarjan’s algorithm sits at the center of that process.

Beacon’s Implementation

Workspace Discovery and Graph Construction

Beacon begins by traversing the workspace using the ignore crate, to honor .gitignore and virtual environment patterns. Each discovered Python file becomes a node represented by a ModuleInfo record containing its URI, logical module name, source root, and dependency set.

The system parses each file’s abstract syntax tree (AST) and extracts both top-level and nested import statements to form directed edges. These edges are stored in an instance of DependencyGraph, which maintains both forward (“imports”) and reverse (“imported by”) links for constant-time queries.

Because Beacon’s document manager also tracks unsaved buffers, the graph always reflects the current editor state rather than the last file-system snapshot.

Running Tarjan’s Algorithm

When the dependency graph changes after edits, additions, or deletions, the system invokes a routine based on Tarjan’s algorithm, implemented as the TarjanState struct. The algorithm iterates through all nodes, assigning indices and lowlink values while maintaining an explicit stack.

Each discovered SCC is a set of URIs representing modules that form a cycle. Single-element SCCs correspond to acyclic modules; multi-element SCCs reveal circular imports. Rather than treating cycles as errors, Beacon uses them as analysis units: type checking and inference occur on a per-SCC basis to ensure internal consistency among mutually dependent files.

Condensation and Topological Sorting

Once SCCs are identified, Beacon constructs a condensation graph where each SCC becomes a node. Edges are reversed (if A imports B, then the condensed graph includes B → A) so that topological sorting can proceed in dependency order.

Kahn’s algorithm is then used to produce an analysis schedule: modules without incoming edges are processed first, followed by those whose dependencies are satisfied. The analyzer consumes this order directly to guarantee deterministic results across runs.

Incremental Re-analysis

When a developer edits a file, the document manager re-parses only the edited module. The graph updates its edges, and Tarjan’s algorithm re-runs to identify affected SCCs. Downstream dependencies are discovered through reverse edges, limiting invalidation to directly dependent modules.

Handling Stubs

Python’s dynamic typing makes stubs (.pyi files) essential for static analysis. Beacon indexes these stubs alongside source files and assigns them module identities in the graph. Tarjan’s traversal captures relationships between implementations and their type stubs.

This means that a cycle spanning a stub and its source file remains visible as a single SCC, such that the analyzer maintains a coherent understanding of symbol origins. A shared StubCache, guarded by RwLock (link), provides thread-safe access to these parsed artifacts during analysis.

Algorithmic and Architectural Interplay

Our integration of Tarjan’s algorithm demonstrates how a theoretically simple procedure can provide architectural clarity in a complex, concurrent system. Several examples of design patterns in practice emerge:

Separation of concerns

The dependency graph handles edge management; Tarjan’s algorithm only classifies structure.Predictable invalidation

SCCs form natural recomputation boundaries.Algorithmic composability.

Tarjan’s results feed directly into Kahn’s algorithm for topological order, yielding a complete pipeline from discovery to analysis scheduling.Concurrency awareness

By keeping Tarjan’s DFS single-threaded but parallelizing parsing and indexing, Beacon maintains correctness without sacrificing performance.

Broader Implications

Tarjan’s algorithm continues to find new life in systems engineering because its structure aligns with the needs of dynamic environments:

Incremental computation: SCCs define minimal recomputation units.

Cycle detection: essential for dependency visualization and modularization.

Deterministic ordering: condensation and topological sorting ensure reproducibility.

Beacon’s case illustrates that these properties are not confined to compilers or static analyzers; they apply equally to live, concurrent systems where files change continuously. By expressing workspace state as a graph and analysis as traversal, Beacon aligns with a lineage of systems that rely on mathematical invariants for predictability and performance.

Tarjan’s algorithm exemplifies the enduring relevance of algorithmic theory in modern software tooling. Its capacity to decompose complex graphs into minimal, interdependent components provides both computational efficiency and conceptual clarity. In the case of Beacon, this algorithm transforms a Python workspace from a collection of files into a structured dependency graph. Each edit, import, or configuration change becomes an update to that graph, and Tarjan’s logic ensures the system remains consistent. The lesson extends beyond any specific implementation: stable, deterministic software often emerges not from new algorithms but from the disciplined application of old ones. Tarjan’s algorithm, through its balance of simplicity and rigor, remains one of the best examples of that principle.

“Tarjan’s Strongly Connected Components Algorithm.” Wikipedia, 31 Oct. 2025. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tarjan%27s_strongly_connected_components_algorithm

Tarjan, Robert E., and Uri Zwick. “Finding Strong Components Using Depth-First Search.” arXiv, 2022. DOI.org (Datacite), https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2201.07197.